- Home

- Vince Bramley

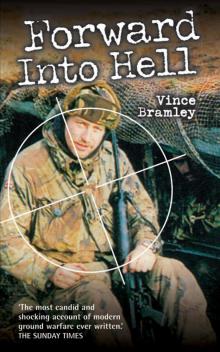

Forward into Hell Page 4

Forward into Hell Read online

Page 4

On 6 May, we sailed south at 1700 hours. Now the lessons in fitness and morale took on a new urgency. We were on our way to do our bit. Our SF GPMGs were mounted around the ship, playing an anti-aircraft role. As we got nearer our destination, our platoon became, with other gunners, the anti-aircraft team. Everything was set up in teams in each company.

The next day Support Company changed its anti-tank Wombat teams into SF teams alongside us. My team split up and I then had only Taff and Steve Ratchford with me. Joining me from the anti-tank teams were Johnny Crow, ‘Skiddy’ Skidmore and Kev Connery. I had known them all for some time from my time in the battalion, so the change wasn’t a big deal. If anything, the change was for the better. Skiddy was a corporal, so he took charge in some ways, with me as second-in-command, although throughout we never looked at each other in terms of rank. All six of us were to stay in B Company.

Saturday, 8 May. That night I got blasted. I felt like getting pissed, so Johnny and I ripped into a good session. Trouble came when I found a lock-in and sat drinking with some Marines and a few lads from C Company. We finished the beer around 0100 hours and I took to the corridor to stagger back to my cabin. As I passed the intercom room, I saw two RMPs sitting there, trying to look smooth, chatting to a young woman, one of the fourteen or so on board. One RMP was a fat-looking wanker in my eyes and I turned to him as I passed the door and said, ‘You fat lump of shit.’ Then I slammed the door and walked off.

Both RMPs came out and screamed, ‘Come here!’

‘Bollocks!’ I said.

They started to chase me down the corridor. I ran down two corridors and into my cabin. I stripped off in seconds and leaped into bed. Seconds later, I could hear them going into each cabin. Reaching ours, they walked in and said, ‘Hello.’

What a pair of wankers, I thought, as I lay pretending to be asleep. No way was I going to be nicked now.

Rawley sat up and murmured, ‘Who the fuck are you?’

‘Oh, we’re looking for a Para that ran this way,’ they said.

‘Well, this is a dead-end and we are trying to sleep, so good night,’ replied Rawley.

After they had closed the door, Rawley waited a few minutes and then turned on the light.

‘What have you done now, Vince?’

I told him with a grin that the fat wankers had annoyed me. We both laughed at the stupid incident. Tommo and Johnny came into the cabin. Johnny’s comment was the same as Rawley’s. ‘What now, Vince?’

Still half pissed, I said, ‘Why does everyone point to me?’

‘’Cause if it isn’t you, it’s TP in this platoon who likes trouble.’

Grinning, I asked, ‘No harm in slagging RMPs, is there?’

Tommo disappeared and returned with yet another bottle of whisky from his unnamed supplier. The four of us sat up drinking until 0400 hours. It was a good thing the next day was Sunday and we had a lie-in. I could not have got out of bed the next morning even if an Exocet had crashed through my porthole. I sobered up around dinnertime.

Monday, 10 May. We had the first briefing that was of real benefit to us. It was confirmed to us that we would be going in, but not before 16 May. We received the latest reports in that briefing in the camped cabin, which stated that over ten thousand enemy troops were in some sort of fortifications in and around Stanley. Our task force was about four thousand strong. The difference in strength caused us to look at each other with concern. I wondered if our brass really knew what they were doing. If the rough estimate of three to one was correct, could the British task force take on and win against the ‘best army in South America’?

Later in the meeting, we got a feel of what might be the first British actions on landing: a possible bridgehead formation somewhere to get supplies ashore. After the briefing, the company went straight into a five-mile run. Back to the routine.

The BBC World Service news on the morning of 11 May brought laughter from all the lads.

‘There is still hope of a political solution to the problem,’ said the newscaster.

Johnny giggled. ‘Perhaps we are going to sunbathe in the ice and snow on the beach-head.’

The BBC news and reporters were becoming a pain. Trusting a reporter was now considered to be like talking to the enemy. Arctic kit was issued and packed. The last hopes of a possible heli-borne assault by the Paras were dashed in the briefing of the day by the platoon commander. We had hoped that we could save face and arrive into battle from the air, instead of clambering on to those bloody landing-craft again.

The evening was passed playing bingo in the bar. Rawley, laughing as usual, cracked, ‘Here we sit, on our way to war, playing fucking bingo. My gang at home won’t believe this.’

All was quiet for the next two or three days. Rumours buzzed as usual, along with moans of ‘Let’s get in and go home.’

The main info we picked up suggested a possible move on 20 May. Our nerves now started. The move south was steady and without any real complications, but the further south we went, the further we were going in. Somehow, I and many others still didn’t quite believe the war was going to happen. We were lost in our own thoughts on many different subjects. Home became secondary now. I thought about the ‘ifs’ and ‘whens’ of our arrival in the exclusion zone and of the landings and battles to follow. Home was not in my immediate thoughts. Survival was.

On the morning of Saturday, 16 May, two twenty-four-hour rations were issued to us for packing, although many of us never unpacked them. Speculation was now rife as to what the landing procedure would be. We were still very much in the dark as to what was happening. But within the next twenty-four hours all the bullshit, rumours and personal beliefs were corrected by the platoon commander.

‘Gents,’ he said, ‘it’s the green light.’ In his hand, he held his orders from the CO and OC of the company and then, on 17 May, I heard for the first time the name Port San Carlos. This was a small farming community on the west coast of East Falkland. History was about to be made and the tiny community was not even aware of the coming invasion, nor were the forty-five Argentinean troops billeted there.

The platoon commander broke down the orders for the gun teams, assigning them their tasks. Steve Ratchford, Taff McNeilly and I were teamed up with Kev Cannery, Johnny Crow and Corporal ‘Skiddy’ Skidmore. Our allotted move was to Company B, 6 Platoon.

At a briefing with 6 Platoon’s commander, Skiddy and I listened to the invasion plan, taking notes for the remainder of our section. We would be cross-decking to the assault ship, HMS Intrepid. Landing-craft would deliver us to a beach called Sandy Bay. We would move up through the settlement to a place called Windy Gap. There, B Company would become the forward line of defence in 3 Para’s bridgehead. About five kilometres inland, we would meet the expected counter-attack, if it came at all, with an air attack almost certainly coming in first. The platoon commander of 6 Platoon explained all this quite calmly. ‘Good luck, gents. This will be over in time for Airborne Forces Day, if we’re lucky.’ Airborne Forces Day is the first weekend of every July in Aldershot and is an annual parade of the Paras past and present.

When I left the briefing and entered my cabin to brief my half, the lads looked at me with wide eyes, in a way that told me they didn’t want to hear anything but good news.

‘Well,’ I said, sitting on the floor. ‘This is going to be one hell of a fucking exercise.’

‘What’s happening now, Vince?’ asked Taff.

‘Well, look at it this way, if we can tab five kilometres inland up this fucking hill,’ I said, pointing to my small photocopied map, ‘then dig in ready for their counter-attack within hours of landing, we should be OK. If we survive the landing, aircraft bombing us and the fucking weather, we can rest at Windy Gap.’

Taff and Steve looked at me and asked, ‘What place?’

‘Windy Gap,’ I repeated. ‘And by the looks of the area on this big detailed map, it looks windy, too.’

After my briefing, including the detai

ls for 3 Para’s, A Company’s and C Company’s positions, the platoon packed their kit into their webbing ready for the expected green light.

The packing of kit was a careful and complicated operation. All kit for the webbing was packed into the usual polythene bags. The rations were broken down and squeezed into the mess tins in the kidney pouches. Socks became cushions for the straps. I wrapped my socks in poly bags, then taped them on the inside of my belt, as padding. My washing and shaving kit, ‘as little as possible’, was packed tightly into a poly bag and wrapped in a third of a torn towel. Packing and repacking to make our webbing as comfortable as possible, we began to psyche ourselves up for the days ahead. It was nerve-racking beyond belief. Yet morale seemed remarkably high throughout the ship, though the laughing and joking among the lads was partly to cover the fear. Not that anyone thought that death was going to hit him. That was for the guy you were talking to.

The platoon sergeant was an incredible pain to us all. Nag, nag, nag, all the time. Our patience is all that saved him. Don’t get me wrong here. We had all served long enough to respect and obey without question, but the guy acted like a wet fart. There, in the middle of the Atlantic, we began to ignore him. The platoon was glad of one thing: he wouldn’t be with any of the gun groups on the day.

On Tuesday, 18 May, we entered the Falklands Zone. The GPMGs were mounted on the decks above. My team and Tommo’s had the sundeck. There, on the first day of our war, we loaded the guns with belts of ammo in readiness for the first expected aircraft attacks. Wind and cold whipped through the layers of clothing we wore.

After two two-hour stints on the decks, we were called below. Our guns were being replaced by the Navy’s. In the corridors of the huge ship that had been our home for nearly six weeks, everyone was extra busy. With our weapons on our shoulders, pushing our way through all the running troops, I saw Paul Reid.

‘Paul,’ I said, ‘what the fuck’s going on now?’

‘Going in early, Vince. Didn’t you know?’

‘Fucking brilliant, ain’t it?’ I replied. ‘There we are on the decks with the brigade preparing to fuck off and leave us.’

Paul grinned. ‘See you in Stanley.’

When we reached our cabins, the platoon commander and sergeant were waiting for the platoon to arrive back from its tasks. Once we were all together, the platoon commander said, ‘Well, lads, we cross-deck in three hours. Get ready now, OK?’

Ammo was dished out to each man. In all, I had six magazines of twenty for my SLR and a belt of over one thousand rounds for the gun. New bandoliers were given out in which fifty rounds were to be placed, but we managed to push and squeeze a hundred into them.

Morale remained high, but our nerves showed as we clambered around the cabin in a frantic panic to get ready. When we had finished, there was nothing to do but sit down and wait. Waiting was the hardest part. I can remember Rawley, Johnny Cook and myself sitting in the cabin for up to an hour without saying a word. It was just eye-talk with smiles.

Tommo opened the door – I can’t remember at what time. ‘Vince, B Company is moving into the kitchen for cross-decking. See yer.’

My nerves disappeared at once. I now had something to do rather than sit. When I placed my webbing on my back, it was so heavy with ammo and personal kit that I thought the buckles were going to bend. It must have weighed sixty pounds. When I picked up the bandoliers and put them over and around my neck I thought my knees would buckle.

Weapon in hand, standing at the door, Johnny looked at me and said, ‘Vince, with all that weight, let’s hope the landing-craft doesn’t sink, ‘cause then you won’t be going anywhere except the seabed!’

‘That’s all I need to hear,’ I said.

We grinned and then smiled, as we said our farewells. ‘See you later, twats.’

My team joined the long line of B Company lads. Slowly, the queue reduced. As I reached the door at the side of the ship, the wind slapped my face with unexpected force. The landing-craft bobbed around fiercely in the choppy sea. A Navy lad grabbed the webbing at my back.

‘When I say, “Jump”, you jump, OK?’ he said.

The craft, half-full and wet with spray, came bobbing back to the side of the ship.

‘Jump!’

In a flash, I jumped, then fell into the craft with my webbing, bergen and SLR. The weight was incredible. At that stage I thought, I hope they don’t expect us to tab far with this little lot.

An hour later, I was half-soaked and fed up with watching all the other poor fuckers falling into the craft. We set off for the Intrepid, about three hundred metres from us. Watching was all we could do. So cramped were we that if anything had happened it would have been like watching a brick sink.

The arrival and sight of the rear of the Intrepid was the start of my war, a war in which my struggle for personal survival was to begin, but also for the survival of my friends and the task force as a whole.

5

WELCOME TO SAN CARLOS

The intercom bleeped into life, requesting all members of 3 Para, including our B Company, to assemble in the galley area. Climbing off the bunk far below the water-line of the Intrepid, my gun team and I put on our already overweight kit and clambered up the small staircase towards the assembly point. I’d always thought the Navy had the life of Riley, but the conditions on that ship made us all appreciate land. Never since that day have I had a bad word for the Navy. The crew, young and eager, acted as perfect hosts during the short time we were on their ship.

When I reached the galley area, I was pissed off to see it crammed with Paras and Marines, slowly filling a gully in front of what seemed to be the sort of turnstile you get at a football match.

The CSM of B Company, Johnny Weeks, handed us all two grenades each. Further along the queue, we were also given two mortar bombs each. Steve Ratchford turned to me and swore in my ear, saying that we were to be ‘donkeys for every bastard going’. I must admit many of us couldn’t figure out how we were to steam up the beach (as in the films) with the amount of kit that we had to carry. Each person was by now carrying about a hundred and twenty pounds. The CSM shouted for us to squeeze up to allow more troops in. Those already in the gully moaned and groaned as we pushed up closer together. An officer standing by a door shouted that we were to hand over the mortar bombs once we landed.

‘Fuck me,’ said Taff. ‘That takes the cake. Carry their kit ashore and hand it to them once we’ve landed.’

A lad from the Mortars smiled and said, ‘Wrong platoon, mate. Don’t think we carry everything, do you?’

Looking all pissed off, Taff sat on his kit waiting for another stupid order.

The area now looked like an overcrowded tube train. The troops had pushed so close together that you could count the blackheads on your neighbour’s face. I sat on my kit, observing the order to ‘Keep all noise down, no talking.’

I looked around me at the hundreds of cammed faces, all with big, wide eyes. Each face told its own story. Each soldier had his own thoughts of the coming battle as the lads quietly sat about waiting. Always waiting – the story of all soldiers. Myself, I couldn’t help but think that it was still a joke and that we wouldn’t be going ashore. My stomach was in knots and the nausea was hard to control. The nervousness running through me was the worst of all. Waiting, waiting for that fucking green light. Many of the lads talked quietly among themselves, probably trying to calm their own nerves. Steve Ratchford rabbited away in my right ear. I don’t remember a single word he said. ‘Doc’ Murdoch sat facing me, pulling faces like a comedian.

‘Fuck off, Doc,’ I said. ‘I’ve got the jitters.’

‘We’ve all got to go somewhere, Vince. Don’t worry.’

Sadly, Doc was to die on Longdon.

It was like waiting for the green light on a para jump, but worse. All the lads had wanted to parachute in, or at least go in by helicopter. Going in on landing-craft was an insult to us. I tried to sleep, without success. Taff managed to nod o

ff and his head rolled from side to side and back and forth. He looked like a puppy dog in the back of a car.

A shout from the same officer as before brought us back to reality again.

‘Listen in: 2 Para have only just landed, without a fight, though one of their guys slipped and broke a leg while embarking into the landing-craft. We are now some time behind schedule, so we must be quicker in the movements now.’

‘Fucking brilliant,’ whispered a Marine.

‘Shut up, Cabbagehead,’ whispered a lad from B Company. ‘You aren’t ashore yet.’

The Marines slowly left the mess hall, the first to embark and ‘do their bit’. Slowly, B Company and its attachments shuffled towards the side door. I stepped out into half-light, on to the pathway leading towards the small landing-craft to which my gun team had been assigned. The OC of B Company and about twenty others clambered into the craft. As we squeezed in, the Navy lads waved for the craft to be lowered into the sea. The smell of the motor didn’t bother me. The cold, fresh air that hit my face felt good after all those smelly, sweaty hours crammed together in the mess hall.

The frustration of waiting and all the hassles of the last six weeks disappeared as we watched, in stunned silence, the battle for Fanning Head to our left. Fanning Head was the Argie OP near San Carlos. The SAS had mounted an attack there, to allow our landings to go ahead without interference. The tracer rounds and naval bombardment on the tip of the bay brought us abruptly into the real world.

‘Jesus, look at that. It’s like a firework display,’ shouted a lad at the front of the craft.

‘Shut up and face the beach coming up.’

We hadn’t noticed we were moving towards the beach. All heads had been turned to watch the battle.

‘Sir,’ said the young radio operator, ‘messages coming through say there’s a tank on our beach.’

‘What?’ screamed the OC.

The word ‘tank’ had caught everyone’s ears. We all looked around and tried to peep over the side to see if a tank did exist. ‘Sit fucking down,’ shouted a sergeant. The craft swayed as we all sat down. ‘Get a GPMG up front, now,’ he shouted.

Forward into Hell

Forward into Hell